What made Vladimir Nabokov tick?

The late great Russian-born novelist Vladimir Nabokov amassed a range of critical comments during his 78 years, more than enough to qualify him as a literary giant and keep his books in print. But most of the assessments have an edge – he was irascible, independent-minded, contradictory, arbitrary, arrogant, tongue-tied, obscene. For such a tumultuous life, he died in opposite conditions: quietly in Montreux, Switzerland, having spent his last 16 years with few friends and almost no family around him.

Making sense of this unique talent has been a hobby of mine since the 1960s, enjoying his quirky prose style, his trilingual puns and his forays into forbidden territory, particularly with Bend Sinister, Lolita, Pnin, Pale Fire and Ada. Have I ever made sense of him? I only scratched the surface.

So the arrival of a new book, Vladimir Nabokov in Context (Cambridge University Press), is most welcome and will appeal to anyone wondering what made this man tick. The title is apt; Nabokov

was very much a product of his times, of his context.

The editors are leading voices in international Slavic studies, David M. Bethea of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and Siggy Frank of Nottingham University in England. They seek to anchor Nabokov in the real world, and show how it related to his novels (ten in Russian and nine in English). They invited 30 hand-picked Nabokov authorities in the U.S. and Europe to contribute digestible essays of about 3000 words each. Academese is held to a minimum.

Bethea and Frank explain in their introduction that they aim to describe “forces pressing in from the world in which Nabokov lived and thought that elicited the remarkable work he produced”.

Nabokov biographer Brian Boyd contributed a cogent overview, noting that Nabokov “insisted on his independence, and on his right not to be dragged into others’ battles”. He criticized the world from the sidelines, however, and relished a good scrap. Boyd quotes Nabokov as having written that “next to the right to create, the right to criticize is the richest gift that liberty of thought and speech can offer”.

Nabokov thought politics best when citizens have the freedom to ignore it. During his years in U.S., “he could afford to pay national politics little heed. His confined his active interest to his resolute anti-Sovietism,” Boyd writes. Thus he was “outraged” at New Yorker magazine’s censoring some of his critiques of Soviet repression.

Of special interest to old Moscow hands will be the essay on samizdat by University of Toronto professor Ann Komaromi. She reports that Nabokov received fan letters from Soviet readers of his writings eager to let him know how highly they regarded his forbidden works. Their support represented a “first attempt to reinstate Nabokov as part of the Russian literary tradition and claim him as their very own Russian writer”. Nabokov rejoiced “in the passion readers brought to his works, even as those Soviet readers strove to read them into their context”. Today, Nabokov’s works are freely available in Russia.

Many of his writings circulated in samizdat typescript or in photographed pages from books smuggled in by Western academics, tourists and diplomats. Lolita was in special demand. Komaromi contributes the best line in the book, quoting an anecdote according to which “the “price for one night with Lolita was five rubles – if the reader promised not to take pictures”.

Among other essays that resonated with me were “Friends and Foes” by Julian W. Connolly of the University of Virginia, “Academia” by Susan Elizabeth Sweeney of College of the Holy Cross, and “Psychoanalysis” by Michal Oklot of Brown University and Matthew Walker of Middlebury College. Nabokov always enjoyed mocking the “Vienna quack”.

And of special interest is “The Cold War” by Will Norman of the University of Kent in England. Norman recommends Nabokov’s essay “The Creative Writer” (available for download at here, produced during his three years as professor at Wellesley College, near Boston. Norman calls it “an extraordinary defense of the power of the irrational imagination in the face of tyrannical demands for conformity”.

Norman remarks that Nabokov liked to deny that he was ever subjected to “the intrusions of history” in his writings. But, says Norman, it is “now clear enough from the vantage point of the twenty-first century that such declarations of autonomy were themselves deeply historical, and that Nabokov’s Cold War had always been hiding in plain sight”.

Besides bringing clarity to Nabokov’s intellectual independence, the discussion of his oeuvre whets the appetite for going back to the best of his books – The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, Bend Sinister, Pnin, Pale Fire and, of course, Lolita. By almost any standard, Vladimir Nabokov left a towering literary legacy.

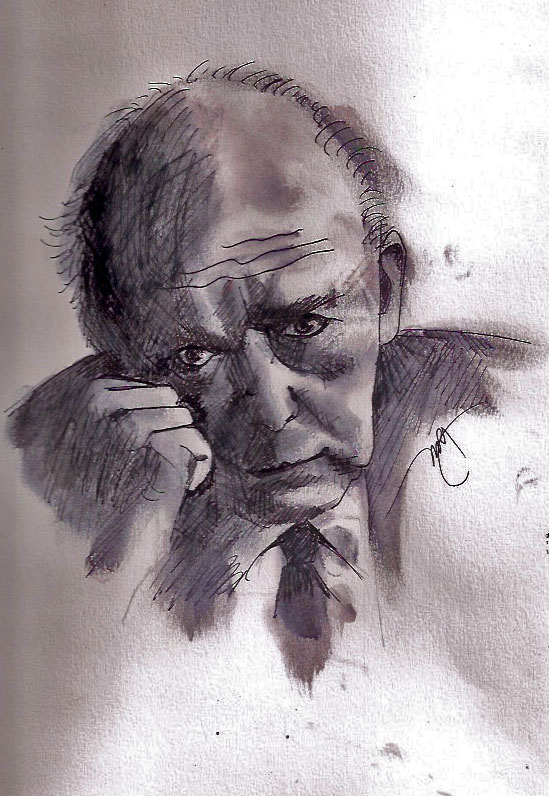

Vladimir Nabokov by the author Michael Johnson:

This article is brought to you by the author who owns the copyright to the text.

Should you want to support the author’s creative work you can use the PayPal “Donate” button below.

Your donation is a transaction between you and the author. The proceeds go directly to the author’s PayPal account in full less PayPal’s commission.

Facts & Arts neither receives information about you, nor of your donation, nor does Facts & Arts receive a commission.

Facts & Arts does not pay the author, nor takes paid by the author, for the posting of the author's material on Facts & Arts. Facts & Arts finances its operations by selling advertising space.

When composer Morton Feldman first heard Atlas Eclipticalis

When composer Morton Feldman first heard Atlas Eclipticalis